Rudolf Koppitz & Heinrich Kühn

EXHIBITION Mar 9 — May 20, 2002

Exhibition Text

The upcoming exhibition at gallery Kicken Berlin will provide the first occasion ever to see and compare masterpieces by Rudolf Koppitz and Heinrich Kühn next to each other. More than fifty rare vintage prints by these great European photographers mirror the history of the first decades of European photography after the turn of the century:

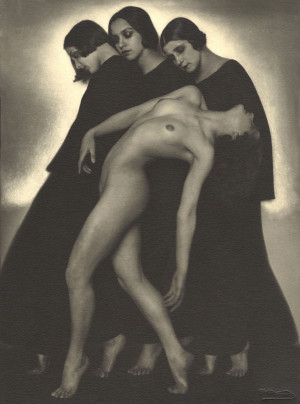

Rudolf Koppitz' (1884-1936) ,,Movement Study" is probably one of the most published and best known pictures in the history of photography. His works were shown in exhibitions frorn Tokyo to New Zealand, New York City to Budapest. In Vienna he was celebrated and inundated with honours yet, after his early death in 1936, Rudolf Koppitz was nearly forgotten. Born into a poor family in northern Moravia, Rudolf Koppitz started his career working for small photo-studios in several parts of the Austrian imperial provinces. In 1912 he dared the decisive step to leave his professional activity and go to school again. He studied at the "Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt" in Vienna, where he already began to teach the following year. Here he made the acquaintance of a circle of colleagues, oriented on works of Fine Art. Among them was J. A. Trcka „Antios", the friend of Egon Schiele - and here he accomplished his first own masterpieces, standing in the tradition of the Viennese Art Nouveau.

At this time he bad acquired his extraordinarily strict - yet harmonious way of composing photographs, and he kept it despite of all changing topics until the end. Whether he photographed the own or alien air-planes from an observation plane during the First World War, whether he depicted reflecting water surfaces, dancers or peasants in their festive-day-dresses, his works characterize a distinct conscience of forms, of lines and surfaces, the play of light and shadows. These features were still accentuated by bis extraordinary championship to master all difficult techniques of art printing. By producing coloured rubber prints, pigment pnints or bromoil transfer prints he created large sheets which his contemporaries regarded as frankly example-giving for photography and its possible claim to reach the high standards of fine art.

Aside his studies of nude female dancers the male nude studies self-portraits which Koppitz sent to many huge exhibitions, fascinated his contemporaries. Showing the photographer in free nature, in high mountains and on rocks in the sea, these photographs testify his enthusiasm for nature.

One of the highlights of the exhibition at Kicken Berlin is the triptych, which the artist himself considered to be central in his artistic work: The „Movement Study" (1925), flanked by „Mother and Child" (1925) - a picture of his wife and daughter - and „In the Bosom of Nature" (1923), showing Koppitz nude in front of the silhouette of the Dead Mountains.

Heinrich Kühn, born 1866 in Dresden, Germany, studied medicine and natural sciences in Berlin ea. In 1890 he settled in Innsbruck, Austria, due to health reasons and stayed in this region for the rest of his life.

Kühn ranks among the most important and influential photographers around the turn of the century. In an era in which the endeavour to elevate photography to the level of an independent art form became the battle-cry of engaged circles in Europe and America, Kühn, with his works of art, set an example for amateurs in the German-speaking world and achieved international recognition. Today his works represent a clear expression of the aspirations of this period, so often misunderstood. They did not seek to imitate painting in terms of appearance and their selection of themes, but, rather, to set a standard which could confirm the artistic quality of photography as a means of expression.

The beginning of the 20th century, the great era of Pictorial Photography, was a time of unprecedented international interest and cooperation in the field of photography. Kühn had a long friendship with the great American photographer Alfred Stieglitz, with whom he corresponded intensively about exhibition projects, technical problems and photo politics. But he also was in touch with other international colleagues as Edward J. Steichen, Frank Eugene Smith and Gertrude Käsebier. Kühn's oeuvre was received with great appreciation in the US. This has been mirrored by the fact that Stieglitz exhibited Kühn's work in his New York gallery "291" and published it in two editions of Camera Work.

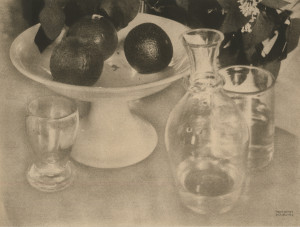

Kühn's pictures reflect a realm, which remained untouched by the external influences of world history in the period 1895- 1944, during which Kühn worked. His cycle of motifs can be found within a limited, repeating sphere - scenery, still- lifes, his family and close acquaintances.

His earliest photographs, large size wall pictures produced according to the gum-bichromate printing method, which Kühn refined, show mainly landscapes in which extensive stretches, interrupted only at isolated intervals - a lonely edifice, a tree or simply a person - create a decorative, rhythmic impression.

Very often he took his motifs from trips to the Netherlands, Italy and Northern Germany, in regions still unaffected and untouched by men. Places like the picturesque sea-shore around Katwijk in the Netherlands offered him the possibility of studying his motifs in great depth and of making detailed notes on lighting conditions, which he later attempted to reproduce in his pictures as a means of expressing his personal feelings. In this regard, he worked like other artists, such as the painter Max Liebermann and the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, both of whom had also been attracted by the solace and charm of this spot as an artistic motif.

No later than around 1903 Kühn's work, now smaller in size, concentrates more on both observations made of the more immediate vicinity around Innsbruck and on his family and shows that his aspiring to the purely decorative is slackening off and fading. One year before, in a book dealing with gum- bichromate printing, Kühn published his intensive involvement with the natural colour scale. This involvement also remained the leitmotif of his later work. Consequently, he expressed his definition of photography in his basic work, Technik der Lichtbildnerei(Photographie Techniques), which he published in 1921: "By photography we understand a pictorial representation expressed in an unbroken intermingling of tones, created and conveyed by the effect of light. A look at Kühn's later pictures shows particularly clearly the extent to which the artist was capable of making full use of the modeling function of light. Within a composition, kept as simple as possible, the essence of the objects or persons portrayed unfolds in an atmosphere both plainly perceptible and recognizable.

Heinrich Kühn was one of the first to provide proof that the camera, with technical virtuosity and artistic feeling, may be used successfully for the creation of a work of art. Kühn himself expressed this in the most suitable terms: "The photographic instrument, the lifeless machine, is compelled by the superior will of the personality to play the role of the subordinate: to a trade is added an artistic moment.