Photographer "Anonymous"

EXHIBITION Dec 8, 2001 — Feb 23, 2002

Exhibition Text

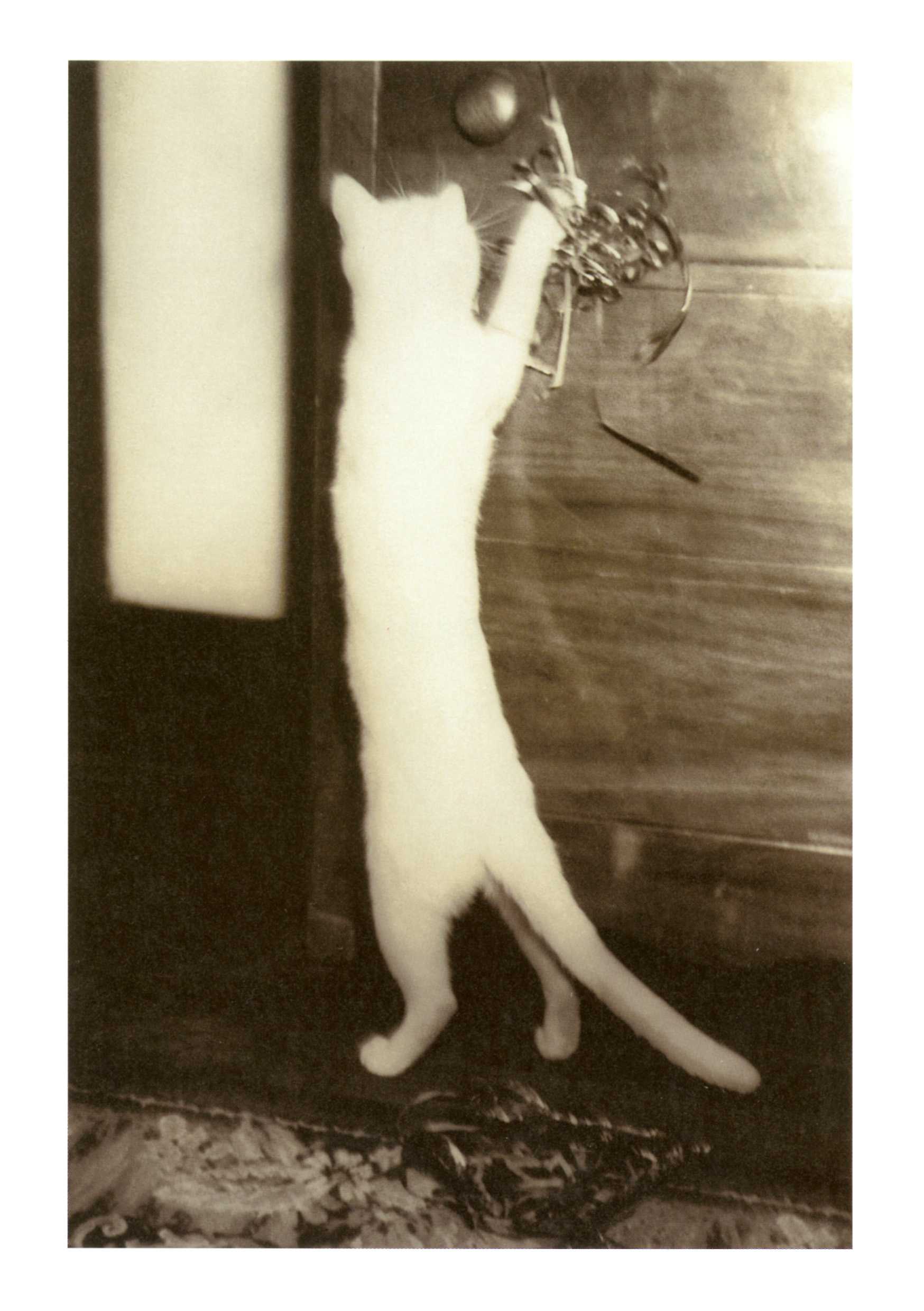

"Seeing is an act of creation. These photographs remind us that the camera can be an extension of genius in the hands of any one of us." (Thomas Walther)

In 1909 Alfred Stieglitz, the pater familias of American art photography, published a list of Twelve Random Dont's in the magazine Photographie Topics, warning amateur photographers not to take themselves too seriously: "Don' t believe you became an artist the instant you received a gift Kodak on Xmas morning," he cautioned. Stieglitz was understandably wary of the ease with which casual snapshooters could roll out of bed one morning and, with a minimum of thought, effort, or agonizing self-reflection, achieve the kind of shimmering greatness he felt was best left to trained professionals. [...] In this view of things, it's difficult, almost impossible, to be an artist only on Sundays and holidays, or only for the briet fraction of a second it takes to make a single exposure that will result in an extraordinary photograph. But the art of photography is notoriously promiscuous: lt doesn't ask for a lifetime of devotion, only for a few moments of passionate attention and voluptuous release. The pictures (...) were made by anonymous amateurs, by the people who collectively make up the most prolific and eclectic artist of this century: Photographer Anonymous. Some were made with the idea of art in mind, others with the idea of cryogenically preserving a pretty girls smile before it gets wiped away by a broken heart. Most of the negatives were handed over to the corner drugstore for processing and printing, where they were routinely rendered as tiny contact prints. As a result, the pictures have the exquisite detail of medieval prayer books and the hand-sized intimacy of playing cards. Each one is a little lure for the Imagination, an enticement, a revelation; some are minor masterpieces.

Taken together, they make the compelling point that genius is something that happens to people. lt may not happen to the same people all the time, and it may happen to some people more than others, but it's not so much a state of being as an event, like a sudden surge of electrical current through copper wires, or a sneeze in the middle of a lecture. Unfortunately, as most artists and anyone working under deadline will grimly confirm, genius, if it happens at all, rarely happens on command. When it does decide to pay a visit, it usually tries to slink by In disguise, posing as a slip of the pen, a wrong note, an accident In the laboratory, a tilted horizon.

Photography, which is a particularly accident-prone medium, has a kind of stochastic genius of its own. lt's random, conjectural, incidental; it doesn't always know exactly what it's doing. Most cameras are simple enough that nearly anyone can use them, but complicated enough that unless you're Ansel Adams, the distance between what you think you see in the viewfinder and the print that comes back from the corner chemist can be astoundingly vast. [ ... ]

Amateur snapshots often bear the traces of a classic slapstick struggle between human and machine, which accounts for part of their charm. We try to persuade the camera to take the pictures we want, and, more often than not, the camera refuses to co-operate. But the harder we try, to paraphrase Beckett, the better we fall. This (exhibition) is filled with successful failures, pictures that sail past their intended targets and into the foggy ether of a different kind of truth. [...]

We take snapshots to commemorate important events, to document our travels, to see how we look in pictures, to eternalize the commonplace, to extract some thread of continuity from the random fabric of experience. We try to impose a kind of order, but sometimes the process backfires, and the messy contingency of the world rushes back in, bringing with it a metaphoric richness that parallels that of dreams. The amateur photo album is an anthology of errors: there are tilted horizons, amputated heads, looming shadows, blurs, lens flares, underexposures, overexposures and inadvertent double exposures. And while not every bungled snapshot is a minor miracle, some seem to tap into a sort of free-floating visual intelligence that runs through the bedrock of the everyday like a vein of gold. [ ... ]

Because of their anonymity and shrouded provenance, many of these pictures hover just on the edge of intelligibility; like riddles, they push us up against the limits of our own thought. [ ... ] Like a Rorschach blot, the photograph rattles the chains of association ad then quietly slips away; it remains, as Diane Arbus once put it, "a secret about a secret."

The pictures selected here date from the 1910s through the 1960s - certainly the golden age of the black and white snapshot but also, and not coincidentally, the era when photography came into its own as an art form uniquely suited for capturing the texture and spirit of modern life. The exhilarating rumble and flash of modernity that bewitched the European New Vision photographers of the 1920s is evident here in the sheer number of trains and automobiles and television sets and dirigibles and airplanes, and in the funhouse distortions and negative prints and bird's-eye views and mirror images and abstractions. The canonical master photographers of the twentieth century seem to haunt these pictures like a pack of jealous ghosts. We sense the austere lyricism of Walker Evans. [...] There are Eugène Atgets, Brassaïs, Cartier-Bressons, Alexander Rodschenkos, Man Rays, Robert Franks, Eugene Meatyards, Diane Arbuses, and Gerhard Richters – all anonymous, all manqué.

Part of the reason these photographs lend themselves so easily to the game of canonical mix and match is that the photographic naifs who made them were not always as naive as we might like to believe - most amateur photographers are neither noble nor savage, and they tend to absorb the styles and traditions of mainstream art photography like sponges, through conscious mimicry or unconscious osmosis. And of

course, the road between high and low runs in both directions. Ever since the turn of the century, artists have been looking at amateur photographs as repositories of a freewheeling formal energy and spontaneity, a charming lack of sophistication and artless authenticity, a palpable sense of quotidian mystery - stylistic qualities that seemed both enviable and eminently up for grabs. There's an old story in the annals of collecting that teils of a New England taxonomist and legendary pack rat who died and left behind two boxes in his desk drawers, one labeled "pieces of string for future use", the other, "pieces of string not worth saving". In the end, all collectors have a touch of this sort of monomania, an irrepressible Impulse to rescue objects from oblivlon, to redeem what others toss aside. These anonymous amateur snapshots - lost or discarded, cleared out of attics or fished out of dumpsters, torn out of family albums that have long out-lived the bloodlines they document - are photography's pieces of string not worth saving. Cut loose from their original, private meanings, they take on the unassailable nobility of orphans and the ineffable enchantment of found poetry. Each of these pictures, in its own irreducible and untranslatable way, teaches us what art can be.

(from an essay by Mia Fineman in: "Other Pictures - Anonymous Photographs from the Thomas Walther Collection" , Twin Palm Publishers 2000)